The Epistemic Insight Initiative helps young people to work with multidisciplinary questions and to appreciate the distinctive contributions of science and other disciplines. When we characterise scientific knowledge we identify that it is a type of knowledge that is supported by direct observations, and also that scientific knowledge informs our thinking about a multidisciplinary question but may not fully address it.

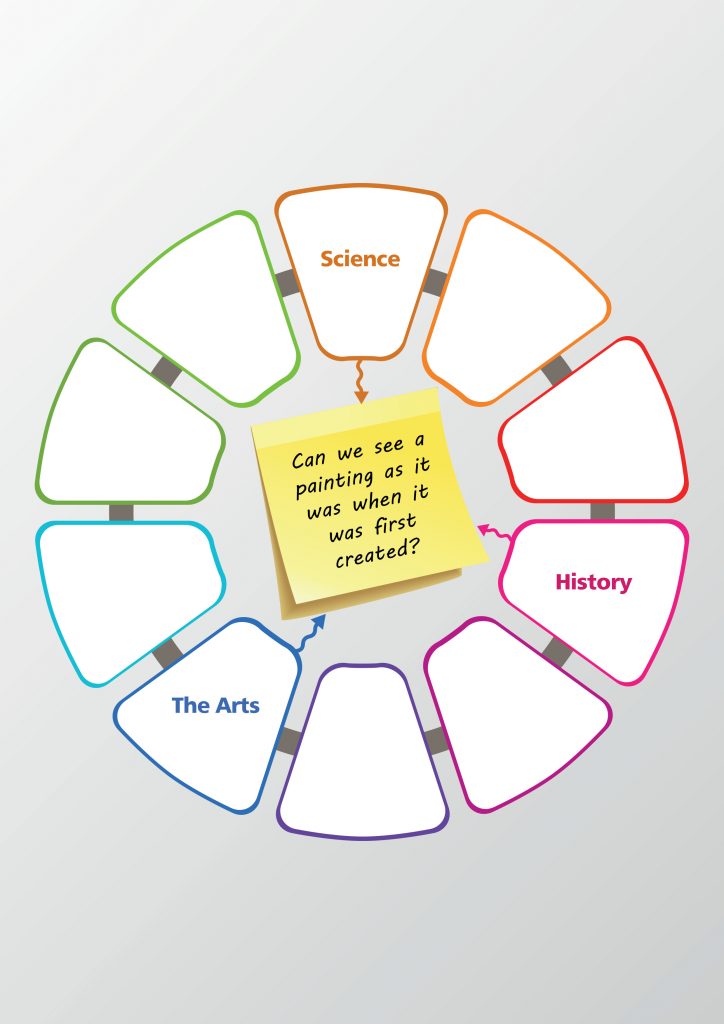

Here’s an example of epistemological analysis – which can be shared with secondary students – to illustrate how a number of disciplines contribute to our understanding of a big question, bridging boundaries of art, science and history.

According to a report by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), there’s a chemist who shone bright red light onto a faded Renoir painting with the aim of helping people to see how it looked before it faded: “Van Duyne, a Northwestern University chemist who developed the world’s most sensitive electron spectroscopy, used this technology to examine the chemical composition of molecules from Pierre-August Renoir’s ‘Madame Léon Clapisson’. He found, from a section of the canvas previously protected by the frame, that Renoir had used carmine lake, a brilliant but light-sensitive red pigment. The scientific investigation and subsequent digital restoration of what Renoir’s original would have looked like is now the subject of a new exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago.”

So we begin with a question that was stimulated by a problem in art. How can we help people to see Renoir’s paintings looking the way they looked when he created them – before they faded. We are told that if the paintings are overpainted to replace the faded colours this is ethically undesirable because it can’t be undone and artistically undesirable because it hides the authentic strokes of the painter.

Can we see a painting looking as the painter intended, hundreds of years ago?

Analysing some of the claims and knowledge in the problem and solution, we can see that there’s a scientific claim and knowledge that the paint seems to be carmine lake, supported by electron spectroscopy and matching with the chemical signatures of paints. The chemical composition of the paint has direct observations to support it.

There’s a claim that it would remove the authenticity of the painting if we paint over it to restore the colours. This seems to rest on an artistic (values) claim that the authenticity of the art is in the brushstrokes of the painter. To validate this we could ask art experts whether this is a shared value in art. So that’s outside science to test using observations, but we can corroborate this claim about values in art in other ways.

In this case study there’s also a historical claim that it’s Renoir who put the paint on the canvas. This can be supported by historical evidence such as letters, testimony, etc., but also not direct observation, so that’s also beyond science to address directly. Science could inform our thinking by testing the age of the paint in the signature, perhaps. But we could also say that this is outside the scope of this problem as we are assuming this is Renoir’s panting here, so there’s also a boundary issue.

There’s the ethical claim that it is better to restore the visual look of the painting without doing something that is a permanent change to the painting. Science can inform our decision if we do some experimentation to discover whether over-painting would be a permanent change. We can’t, however, use direct observations to judge whether a permanent change is good or bad. So science can inform our decision about whether to overpaint, but not tell us if it’s good or bad to do so.

There’s also an aesthetic claim about overpainting hiding brushstrokes. We could test this in a quasi-scientific way by adding paint and asking people what they see. For example, we could say, once 50% of 100 people say they can’t see brushstrokes, they’re ‘hidden’. It’s quasi-scientific because the nature of the question requires us to look for the subjective experience, so we are getting this by asking people to say what they think they see.

There’s a creative moment where the chemist applies scientific knowledge and says that, if we shine bright red light on the faded canvas to compensate for colour-loss, the observer’s eyes will see the painting looking apparently brighter as it was. We can do quasi scientific experiments with faded and non-faded colour boards and light.

The claim that we now see the painting looking like it originally did is not directly testable. There’s a case to say that the ‘restored’ version is more like the original based on the colour boards, but to really test this we’d like to transport a group of observers to and fro in time to see both images. That might reveal a problem such as that in the past the light in the gallery was not the same as the light in a gallery today.

At this point we see that the original question has some ambiguity: Do I want to see the painting as Renoir saw it in his studio? Or as viewers saw it when displayed in a gallery? Or as I would see it in a gallery today? That points out that, if we change the goal a bit, it changes the answer we say is ‘right’.

Science informed our thinking about lots of parts of this story, and within the bigger multifaceted issue, we can say that some questions are more amenable to science than others.